COP15 to the UN Convention on Biological Diversity: Quick history and relation to ATLANTIS

Global biodiversity has declined rapidly in the past decades, the WWF’s Living Planet Report of 2022 stated that wildlife populations declined on average 69% since 1970. In light of this issue, the 15th meeting of the Conference of Parties (COP15) to the UN Convention of Biological Diversity (CBD) was held from the 7th to the 19th of December 2022 in Montreal, Canada. The main result of COP15 is the final text of Kunming-Montreal global biodiversity framework, including four long-term goals to be achieved in 2050, and 23 targets that, if achieved by 2030, should help the party nations towards achieving the long-term goals. In this article we shortly review the history leading up to the COP15 to CBD and how our project team, ATLANTIS, supports the tasks ahead.

Short history of the UN Convention of Biological Diversity

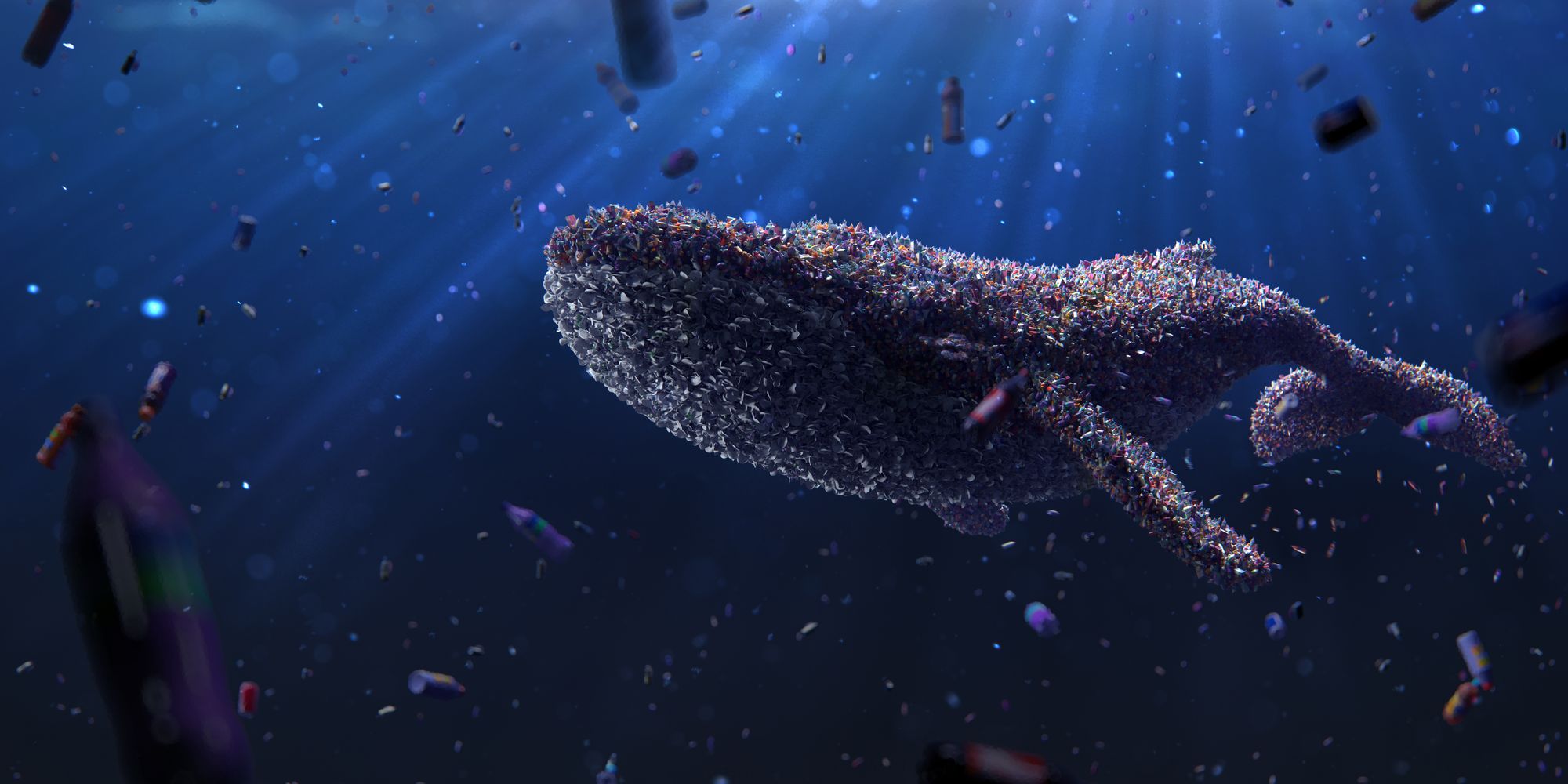

The history of the UN CBD began together with the more known UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (FCCC) at the Earth Summit in 1992. Whereas the FCCC focus on combating greenhouse gas emissions, the CBD combats loss of biodiversity by developing national strategies on sustainable use and conservation of biological resources, i.e. the sustainable interaction between industry and ecosystems for which we, in our field (Industrial Ecology), develop decision-tools to achieve, e.g. integrated assessment models (IAMs), material flow analysis (MFA), input-output analysis (IO), and life cycle assessments (LCAs). The CBD is meant to cover all ecosystems, species, and genetic resources. It also follows the precautionary principle, which means that the lack of scientific certainty should not excuse any postponing of measures needed to avoid or alleviate impacts on biodiversity. The Nairobi Final Act entered into force on the 29th of December 1993 with 168 signatures. In its 2nd resolution it mentions to “To identify components of biological diversity of importance for its conservation and the sustainable use of its components” and to “identify processes and activities which have or are likely to have an adverse impact on biological diversity”.

Today we have identified five key drivers of biodiversity decline: Changes in land and sea use, climate change, pollution, direct exploitation of natural resources, and invasive species. To these drivers we have also evaluated which human activities are related and estimated the economic value of biodiversity as our natural resource. This December, 195 countries ratified the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, along with the EU. Of these, all UN member states have ratified the treaty except the US, although they have made programs for species conservation and recovery. But in between the Nairobi Final Act in 1993 and our current Kunming-Montreal goals, was the equally ambitious Aichi goals that we mostly failed to achieve.

The UN’s “decade on biodiversity” from 2011-2020 started at the 2010’s International Year of Biodiversity, a “celebration of biodiversity” meant to increase the awareness and importance of biodiversity. It coincided with the failure of the 2010 biodiversity target aimed to halt the decline of biodiversity loss – a target that was far from reached. The next targets until 2020 were imbedded in the Aichi Biodiversity Targets. The first strategic goal (A) wanted to “address the underlying causes of biodiversity loss…” which has impacts on the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework agreed in COP15 where the goals now focus on more measurable actions as the causes have now been identified. The other 4 Aichi goals relate to reduced biodiversity pressure, and improved and enhanced ecosystem diversity and services, which were to be achieved through enhanced implementation through better planning, knowledge management, and capacity building. However, we failed to reach these goals, critics state that they were too vaguely formulated. Similarly, the Kunming-Montreal goals regards ecosystem and biodiversity health, halting of species extinctions, and presents biodiversity as a resource valuable to human society that should be used sustainably. But there is a different tone in the Kunming-Montreal goals compared to the Aichi goals.

The progress seen in the Kunming-Montreal goals

Whereas the Aichi targets have been critiqued because they “included vague language and did not hold countries to specific action”, the Kunming-Montreal goals present more specific goals than seen before, and has both short termed targets (2030) while the goals are long term (2050). National Biodiversity Strategies and Action Plans (NBSAPs) has been made by most participating parties and developed since the beginning of CBD. The NBSAPs are meant help nations carry out the necessary actions needed to reach the Aichi targets and had to be made on a national level to account for the different needs and challenges of different nations. But despite many nations having successfully implemented a strategic framework, the Aichi targets were not reached in 2020 and deemed a failure. Reflecting on what caused the failure, two major perspectives have been considered when setting up the Kunming-Montreal goals:

1. The Aichi targets were ambitious and inspired parties to make an effort, but they were also vaguely described and mostly with no benchmark to compare progress. One target, target 11, was specific: "By 2020, at least 17 per cent of terrestrial and inland water, and 10 per cent of coastal and marine areas… are conserved…” And indeed 15 and 8 percent was achieved by 2020. It is a failure, but also a proof of progress.

2. The Aichi targets left it up to each nation’s environmental ministries to finance the measures needed to reach the targets. Target 20 aims at substantially increasing mobilization of financial resources but has no specific value and is also subject to change. Therefore, with the lack of agreement on international economic needs, especially developing countries were unable to build the capacity needed to reach the targets.

In the Kunming-Montreal targets you will find more specific and measurable benchmarks. E.g., by 2030, 30 percent of ecosystems are under effective restoration, and 30 percent of areas of biodiversity importance are conserved and managed. And human induced extinctions are halted, establishment rates of known invasive species are reduced by 50 percent in 2030 and tenfold in 2050, and most notably the estimated economic finance gap of 700 billion USD per year is closed.

Time to manage those that “roll up their sleeves”

The UNEP executive director, Inger Andersen, said “it’s time to roll up our sleeves” which could be an almost direct message to Greta Thunberg that now we will come to the action. We have spent decades identifying and quantifying the problem, which to be fair should not have been a necessary primer of action, since we supposedly should follow the precautionary principle. Nonetheless, now that there are specific targets with measurable progress and benchmarks, we can at least expect the parties to be held more accountable to their promises. Also, we can add the specific targets to our NBSAPs and evaluate amongst each other, and over time. What history has shown is that specific and measurable targets have led to better progress, and creating these quantifiable targets is what we have now come a step closer to.

But new critiques are already in place, amongst others the executive secretary of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES): Dr. Anne Larigauderie. She regrets to have only agreed on the “30x30”pledge, i.e. the focus on conserving 30 percent of nature. Whereas some believe to be close to the target already, making this a clearer but non-influential target, the specific formulation of the target was in debate before it was even ratified. For example, the UK believed to have protected 26 percent of their ecosystem area, but the Wildlife and Countryside Link declared that only 3.22 and 8 percent of land and sea area, respectively, is effectively protected. Therefore, the formulation of how we indicate progress towards our targets should also be standardized – such work has already been done for the Aichi targets, although only as guidelines. It is my hope that we will see stronger formulations for the Kunming-Montreal targets in a similar manner but as more than guidelines.

On one side we find that specifically quantified targets and goals give way for better results, but simultaneously we must allow nations, sectors, industries, companies, and even households to set their own agenda on how to reach these targets as the best path is context dependent – in other words, we cannot be too specific! Meanwhile, we must ensure that the communication between these entities is transparent and continuous so that they can reach the targets symbiotically rather than in competition. And for this to succeed we must have tools and standards that enable decision-making across these entities.

How ATLANTIS will help reach the Kunming-Montreal targets

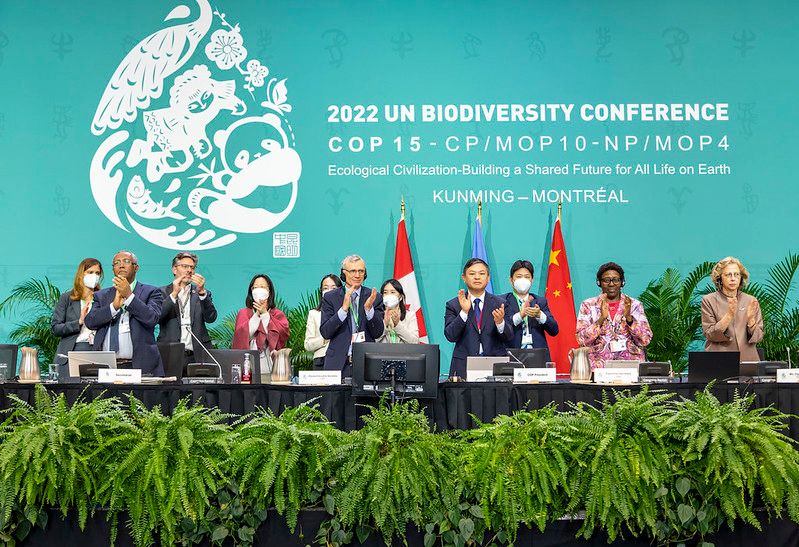

The ATLANTIS project is tasked with creating “ecological indicators” in the marine environment specifically focused to be compatible within the “Life Cycle Assessment” framework. Ecological indicators are meant to communicate the impacts of human activities on our ecosystem. Life Cycle Assessments calculate on all energy and material flows between our ecosystems and the “life cycle” of a product or service. Such a life cycle is usually said to be from the first acquisition of resources needed for production (like fuels and metals) until it is discarded (reused, recycled, or disposed of), and includes all steps in between (like use and transport). Thereby, we develop tools that can help decision-makers evaluate if one choice is more sustainable than another and highlight where to invest resources for further development towards a sustainable value chain. This means that each consumer and producer know of the biodiversity impacts related to a strategic choice or product bought, given that the life cycle assessment is clear and transparent, and that the impact on biodiversity is included in the LCA framework when used.

However, the life cycle assessment framework is continuously in development. Whereas impacts related to global warming are considered reliable indicators, indicators on other biodiversity threats are fully missing in the framework. We in ATLANTIS are developing the first indicators for invasive species, and macro-plastic pollution, and we relate these impacts along other impacts to ecosystem services – all for the marine biosphere. This is a step closer to quantify our footprint on two of the five key drivers on biodiversity decline: Invasive species, and pollution. In addition, the impacts are assessed throughout the value chains thereby giving an overview of the impactors in different sectors and industries, allowing for communication between the right stakeholders as the material or energy flows become highlighted in the value chains and so you are able to map relevant connections that needs to be developed to achieve your own target. We are creating all indicators on a regionalised resolution meaning that we differentiate between impacts based on the context of their location. Therefore, you could very well find that you are able to reduce your impacts caused by introducing invasive alien species, by either changing trade routes or communicating to your shipping partners that there are impacts that needs to be alleviated and the change documented.

In my personal perspective on life cycle assessment, it is not meant to “stamp” anyone as sustainable or not, but rather it is a tool that allows for better screening and communication of impacts between stakeholders such that we in collaboration can move towards the best sustainable choices. An example related to our Kunming-Montreal goals is Norway’s NBSAP stating that: “We are responsible for the environmental pressure Norwegian activities cause outside the country’s borders through trade and investment. Norway’s efforts to reduce pressure from Norwegian activities in other countries are therefore an important part of its national policy for biodiversity at global level.” The mentioned pressures can be found using life cycle assessment, and therefore it is paramount that we include the key drivers of biodiversity decline.