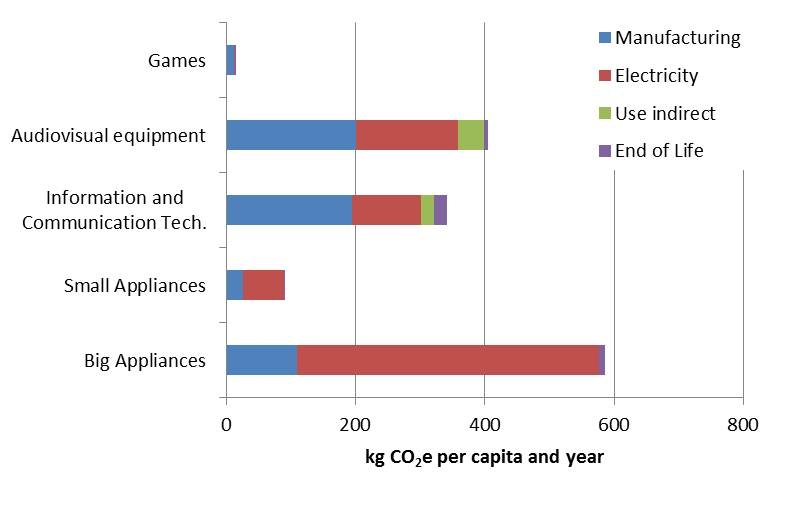

PC and TV purchases shape EEE carbon footprint

The rapid proliferation of electronic entertainment and communication equipment has eclipsed traditional household appliances like washing machines and refrigerators as the equipment with the highest residential carbon footprint; apart from heating, hot water and lighting.

The Norwegian state broadcaster sent a wonderful story on our new study: a home electronics seller is interviewed, listing the number of TVs his customers have in a household: in the living room, the kitchen, the bedroom and each of the kids rooms. He also confirms that these are replaced frequently. Our study showed that the manufacture of electronics purchased by Norwegian households causes about 350 kg of CO2 per person and year. Assuming a relatively clean Norwegian or Nordic electricity mix, this is more than is caused by household appliances. The development shows a reversal compared to conventional wisdom in energy analysis: for this equipment, the emissions during manufacturing are really more important than those during the use phase. And what energy analysts have previously been labelled the “miscellaneous” category is now more important than (or of comparable importance with the relatively dirty EU electricity mix as) what used to be the big-ticket items: freezers, refrigerators, washing machines, dishwashers, and electric ovens and ranges. A more detailed summary of the paper was published in KLIMA andChemical & Engineering News.

The study triggered a number of reactions by Norwegian actors that were reported by the Norwegian broadcaster. One of the factors we criticized was the high acquisition rate, suggesting that relatively new and working equipment is discarded. An environmental organization hence argued for an extension of the mandatory warranty period to 5 years. However, most reactions were prompted by the comments of climate policy professor Jørgen Randers, famous for being a co-author of the seminal “Limits to growth” report. He argued that there was no point in focusing on PCs and TVs, as there would be little gain and people want to have those anyway. Instead, he suggested we should focus our efforts on electric vehicles.

This is what happens in a hectic media day: Randers really missed the deeper implications of our research. We argue that one reason why operational energy use went down was the successful policy of the EU to increase the efficiency and decrease the stand-by losses of energy-using equipment. Despite of these successes, we see a high carbon footprint from EEE, electric and electronic equipment. Just now, it is coming from something else: new consumption of equipment we did not use before, like computers, home electronics, multiple TV sets. In addition, the rapid technological obsolescence due to technological improvement drives the turn-over especially for flat-panel TVs, PCs and mobile phones, which is also why longer warranties will not help. I do think this instance demonstrates on a specific case a mechanism that happens more widely: that we, with our ingenuity, constantly find new ways to stimulate and satisfy our curiosity which create consumption that comes in addition to what we had before. Like other stuff, this is made out of materials using energy to shape it, and it thus causes GHG emissions. It is a demonstration that efficiency gains and better technology alone will not be sufficient to save us from climate change.

The work on household electronics was conducted by MSc student Charlotte Roux under my supervision and I checked, modified and wrote up the results. It was published in Environmental Science & Technology (ES&T). PhD students Anders Arvesen, Ryan Bright and I just published a discussion of the larger mechanisms counteracting climate mitigation efforts, based on reading in a PhD course.

And by the way, I learned today that our Carbon Footprint of Nations study from 2009 was still among the top downloaded papers in ES&T in the third quarter of 2001. We are being cited in about 25 other articles in peer-reviewed scientific journals.